Electric Fields of Continuous Charge Distributions Arc

Chapter 5. Electric Charges and Fields

5.5 Calculating Electric Fields of Charge Distributions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what a continuous source charge distribution is and how it is related to the concept of quantization of charge

- Describe line charges, surface charges, and volume charges

- Calculate the field of a continuous source charge distribution of either sign

The charge distributions we have seen so far have been discrete: made up of individual point particles. This is in contrast with a continuous charge distribution, which has at least one nonzero dimension. If a charge distribution is continuous rather than discrete, we can generalize the definition of the electric field. We simply divide the charge into infinitesimal pieces and treat each piece as a point charge.

Note that because charge is quantized, there is no such thing as a "truly" continuous charge distribution. However, in most practical cases, the total charge creating the field involves such a huge number of discrete charges that we can safely ignore the discrete nature of the charge and consider it to be continuous. This is exactly the kind of approximation we make when we deal with a bucket of water as a continuous fluid, rather than a collection of [latex]{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}[/latex] molecules.

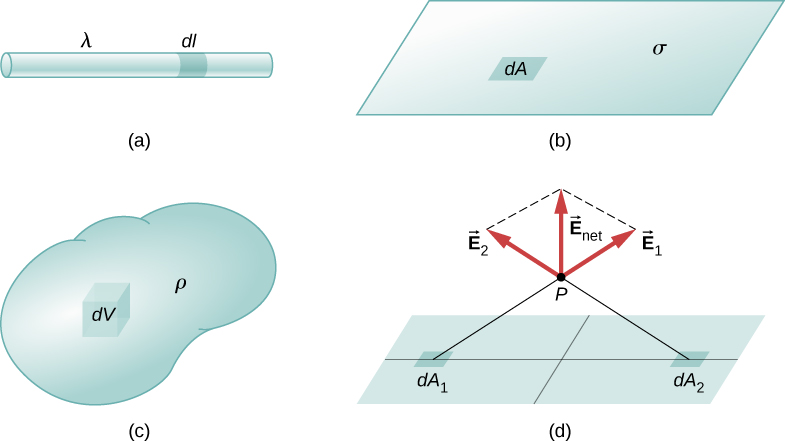

Our first step is to define a charge density for a charge distribution along a line, across a surface, or within a volume, as shown in Figure 5.22.

Definitions of charge density:

- [latex]\lambda \equiv[/latex] charge per unit length (linear charge density); units are coulombs per meter (C/m)

- [latex]\sigma \equiv[/latex] charge per unit area (surface charge density); units are coulombs per square meter [latex]\left(\text{C}\text{/}{\text{m}}^{2}\right)[/latex]

- [latex]\rho \equiv[/latex] charge per unit volume (volume charge density); units are coulombs per cubic meter [latex]\left(\text{C}\text{/}{\text{m}}^{3}\right)[/latex]

Then, for a line charge, a surface charge, and a volume charge, the summation in Equation 5.4 becomes an integral and [latex]{q}_{i}[/latex] is replaced by [latex]dq=\lambda dl[/latex], [latex]\sigma dA[/latex], or [latex]\rho dV[/latex], respectively:

[latex]\text{Point charge:}\phantom{\rule{2em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\sum _{i=1}^{N}\left(\frac{{q}_{i}}{{r}^{2}}\right)\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]

[latex]\text{Line charge:}\phantom{\rule{2em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{line}}\left(\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\right)\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]

[latex]\text{Surface charge:}\phantom{\rule{2em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{surface}}\left(\frac{\sigma dA}{{r}^{2}}\right)\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]

[latex]\text{Volume charge:}\phantom{\rule{2em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{volume}}\left(\frac{\rho dV}{{r}^{2}}\right)\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]

The integrals are generalizations of the expression for the field of a point charge. They implicitly include and assume the principle of superposition. The "trick" to using them is almost always in coming up with correct expressions for dl, dA, or dV, as the case may be, expressed in terms of r, and also expressing the charge density function appropriately. It may be constant; it might be dependent on location.

Note carefully the meaning of r in these equations: It is the distance from the charge element [latex]\left({q}_{i},\lambda dl,\sigma dA,\rho dV\right)[/latex] to the location of interest, [latex]P\left(x,y,z\right)[/latex] (the point in space where you want to determine the field). However, don't confuse this with the meaning of [latex]\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]; we are using it and the vector notation [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] to write three integrals at once. That is, Equation 5.9 is actually

[latex]{E}_{x}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{{\int }_{\text{line}}\left(\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\right)}_{x},\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}{E}_{y}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{{\int }_{\text{line}}\left(\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\right)}_{y},\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}{E}_{z}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{{\int }_{\text{line}}\left(\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\right)}_{z}.[/latex]

Example

Electric Field of a Line Segment

Find the electric field a distance z above the midpoint of a straight line segment of length L that carries a uniform line charge density [latex]\lambda[/latex].

Strategy

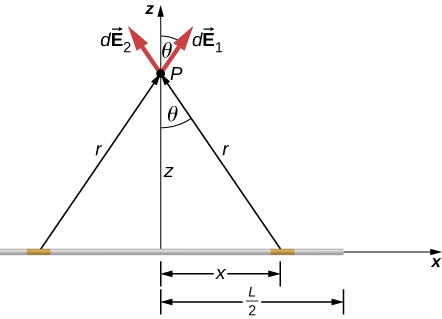

Since this is a continuous charge distribution, we conceptually break the wire segment into differential pieces of length dl, each of which carries a differential amount of charge [latex]dq=\lambda dl[/latex]. Then, we calculate the differential field created by two symmetrically placed pieces of the wire, using the symmetry of the setup to simplify the calculation (Figure 5.23). Finally, we integrate this differential field expression over the length of the wire (half of it, actually, as we explain below) to obtain the complete electric field expression.

Solution

Show Answer

Before we jump into it, what do we expect the field to "look like" from far away? Since it is a finite line segment, from far away, it should look like a point charge. We will check the expression we get to see if it meets this expectation.

The electric field for a line charge is given by the general expression

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{line}}\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}.[/latex]

The symmetry of the situation (our choice of the two identical differential pieces of charge) implies the horizontal (x)-components of the field cancel, so that the net field points in the z-direction. Let's check this formally.

The total field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)[/latex] is the vector sum of the fields from each of the two charge elements (call them [latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{1}[/latex] and [latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{2}[/latex], for now):

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)={\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{1}+{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{2}={E}_{1x}\hat{\textbf{i}}+{E}_{1z}\hat{\textbf{k}}+{E}_{2x}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)+{E}_{2z}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Because the two charge elements are identical and are the same distance away from the point P where we want to calculate the field, [latex]{E}_{1x}={E}_{2x},[/latex] so those components cancel. This leaves

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)={E}_{1z}\hat{\textbf{k}}+{E}_{2z}\hat{\textbf{k}}={E}_{1}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}+{E}_{2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

These components are also equal, so we have

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\hfill \stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)& =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\int \frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}+\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\int \frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{0}^{L\text{/}2}\frac{2\lambda dx}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

where our differential line element dl is dx, in this example, since we are integrating along a line of charge that lies on the x-axis. (The limits of integration are 0 to [latex]\frac{L}{2}[/latex], not [latex]-\frac{L}{2}[/latex] to [latex]+\frac{L}{2}[/latex], because we have constructed the net field from two differential pieces of charge dq. If we integrated along the entire length, we would pick up an erroneous factor of 2.)

In principle, this is complete. However, to actually calculate this integral, we need to eliminate all the variables that are not given. In this case, both r and [latex]\theta[/latex] change as we integrate outward to the end of the line charge, so those are the variables to get rid of. We can do that the same way we did for the two point charges: by noticing that

[latex]r={\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}[/latex]

and

[latex]\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =\frac{z}{r}=\frac{z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}}.[/latex]

Substituting, we obtain

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\hfill \stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)& =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{0}^{L\text{/}2}\frac{2\lambda dx}{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{0}^{L\text{/}2}\frac{2\lambda z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}dx\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{2\lambda z}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left[\frac{x}{{z}^{2}\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{x}^{2}}}\right]{|}_{0}^{L\text{/}2}\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

which simplifies to

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda L}{z\sqrt{{z}^{2}+\frac{{L}^{2}}{4}}}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Significance

Notice, once again, the use of symmetry to simplify the problem. This is a very common strategy for calculating electric fields. The fields of nonsymmetrical charge distributions have to be handled with multiple integrals and may need to be calculated numerically by a computer.

Check Your Understanding

How would the strategy used above change to calculate the electric field at a point a distance z above one end of the finite line segment?

Show Solution

We will no longer be able to take advantage of symmetry. Instead, we will need to calculate each of the two components of the electric field with their own integral.

Example

Electric Field of an Infinite Line of Charge

Find the electric field a distance z above the midpoint of an infinite line of charge that carries a uniform line charge density [latex]\lambda[/latex].

Strategy

This is exactly like the preceding example, except the limits of integration will be [latex]\text{−}\infty[/latex] to [latex]\text{+}\infty[/latex].

Solution

Show Answer

Again, the horizontal components cancel out, so we wind up with

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{−}\infty }^{\infty }\frac{\lambda dx}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \hat{\textbf{k}}[/latex]

where our differential line element dl is dx, in this example, since we are integrating along a line of charge that lies on the x-axis. Again,

[latex]\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =\frac{z}{r}=\frac{z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}}.[/latex]

Substituting, we obtain

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\hfill \stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)& =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{−}\infty }^{\infty }\frac{\lambda dx}{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{−}\infty }^{\infty }\frac{\lambda z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{x}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}dx\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{\lambda z}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\left[\frac{x}{{z}^{2}\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{x}^{2}}}\right]|}_{\text{−}\infty }^{\infty }\hat{\textbf{k}},\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

which simplifies to

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2\lambda }{z}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Significance

Our strategy for working with continuous charge distributions also gives useful results for charges with infinite dimension.

In the case of a finite line of charge, note that for [latex]z\gg L[/latex], [latex]{z}^{2}[/latex] dominates the L in the denominator, so that Equation 5.12 simplifies to

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\approx \frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda L}{{z}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

If you recall that [latex]\lambda L=q[/latex], the total charge on the wire, we have retrieved the expression for the field of a point charge, as expected.

In the limit [latex]L\to \infty[/latex], on the other hand, we get the field of an infinite straight wire, which is a straight wire whose length is much, much greater than either of its other dimensions, and also much, much greater than the distance at which the field is to be calculated:

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2\lambda }{z}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

An interesting artifact of this infinite limit is that we have lost the usual [latex]1\text{/}{r}^{2}[/latex] dependence that we are used to. This will become even more intriguing in the case of an infinite plane.

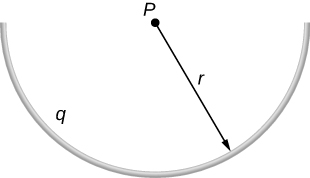

Example

Electric Field due to a Ring of Charge

A ring has a uniform charge density [latex]\lambda[/latex], with units of coulomb per unit meter of arc. Find the electric potential at a point on the axis passing through the center of the ring.

Strategy

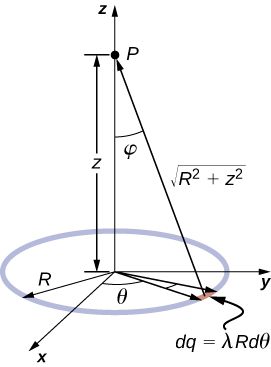

We use the same procedure as for the charged wire. The difference here is that the charge is distributed on a circle. We divide the circle into infinitesimal elements shaped as arcs on the circle and use polar coordinates shown in Figure 5.24.

Solution

Show Answer

The electric field for a line charge is given by the general expression

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{line}}\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}.[/latex]

A general element of the arc between [latex]\theta[/latex] and [latex]\theta +d\theta[/latex] is of length [latex]Rd\theta[/latex] and therefore contains a charge equal to [latex]\lambda Rd\theta .[/latex] The element is at a distance of [latex]r=\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{R}^{2}}[/latex] from P, the angle is [latex]\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\varphi =\frac{z}{\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{R}^{2}}}[/latex], and therefore the electric field is

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)\hfill & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{line}}\frac{\lambda dl}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{0}^{2\pi }\frac{\lambda Rd\theta }{{z}^{2}+{R}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{z}{\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{R}^{2}}}\hat{\textbf{z}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda Rz}{{\left({z}^{2}+{R}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{z}}{\int }_{0}^{2\pi }d\theta =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2\pi \lambda Rz}{{\left({z}^{2}+{R}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{z}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{{q}_{\text{tot}}z}{{\left({z}^{2}+{R}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{z}}.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

Significance

As usual, symmetry simplified this problem, in this particular case resulting in a trivial integral. Also, when we take the limit of [latex]z>>R[/latex], we find that

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\approx \frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{{q}_{\text{tot}}}{{z}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{z}},[/latex]

as we expect.

Example

The Field of a Disk

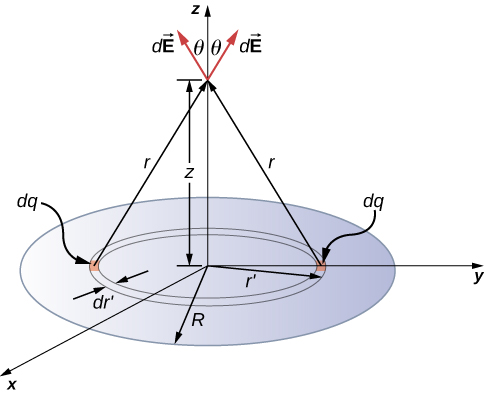

Find the electric field of a circular thin disk of radius R and uniform charge density at a distance z above the center of the disk (Figure 5.25)

Strategy

The electric field for a surface charge is given by

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{surface}}\frac{\sigma dA}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}.[/latex]

To solve surface charge problems, we break the surface into symmetrical differential "stripes" that match the shape of the surface; here, we'll use rings, as shown in the figure. Again, by symmetry, the horizontal components cancel and the field is entirely in the vertical [latex]\left(\hat{\textbf{k}}\right)[/latex] direction. The vertical component of the electric field is extracted by multiplying by [latex]\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta[/latex], so

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{\text{surface}}\frac{\sigma dA}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

As before, we need to rewrite the unknown factors in the integrand in terms of the given quantities. In this case,

[latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\hfill dA& =\hfill & 2\pi {r}^{\text{′}}d{r}^{\prime }\hfill \\ \hfill {r}^{2}& =\hfill & {{r}^{\prime }}^{2}+{z}^{2}\hfill \\ \hfill \text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta & =\hfill & \frac{z}{{\left({{r}^{\prime }}^{2}+{z}^{2}\right)}^{1\text{/}2}}.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

(Please take note of the two different "r's" here; r is the distance from the differential ring of charge to the point P where we wish to determine the field, whereas [latex]{r}^{\prime }[/latex] is the distance from the center of the disk to the differential ring of charge.) Also, we already performed the polar angle integral in writing down dA.

Solution

Show Answer

Substituting all this in, we get

[latex]\begin{array}{cc}\hfill \stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(P\right)& =\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{\int }_{0}^{R}\frac{\sigma \left(2\pi {r}^{\prime }d{r}^{\prime }\right)z}{{\left({{r}^{\prime }}^{2}+{z}^{2}\right)}^{3\text{/}2}}\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \\ & =\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left(2\pi \sigma z\right)\left(\frac{1}{z}-\frac{1}{\sqrt{{R}^{2}+{z}^{2}}}\right)\hat{\textbf{k}}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

or, more simply,

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left(2\pi \sigma -\frac{2\pi \sigma z}{\sqrt{{R}^{2}+{z}^{2}}}\right)\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Significance

Again, it can be shown (via a Taylor expansion) that when [latex]z\gg R[/latex], this reduces to

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)\approx \frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\sigma \pi {R}^{2}}{{z}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{k}},[/latex]

which is the expression for a point charge [latex]Q=\sigma \pi {R}^{2}.[/latex]

Check Your Understanding

How would the above limit change with a uniformly charged rectangle instead of a disk?

Show Solution

The point charge would be [latex]Q=\sigma ab[/latex] where a and b are the sides of the rectangle but otherwise identical.

As [latex]R\to \infty[/latex], Equation 5.14 reduces to the field of an infinite plane, which is a flat sheet whose area is much, much greater than its thickness, and also much, much greater than the distance at which the field is to be calculated:

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{\sigma }{2{\epsilon }_{0}}\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Note that this field is constant. This surprising result is, again, an artifact of our limit, although one that we will make use of repeatedly in the future. To understand why this happens, imagine being placed above an infinite plane of constant charge. Does the plane look any different if you vary your altitude? No—you still see the plane going off to infinity, no matter how far you are from it. It is important to note that Equation 5.15 is because we are above the plane. If we were below, the field would point in the [latex]\text{−}\hat{\textbf{k}}[/latex] direction.

Example

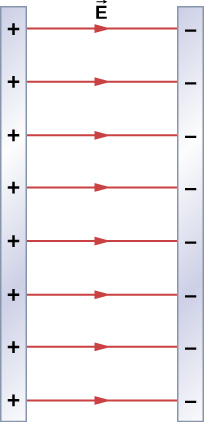

The Field of Two Infinite Planes

Find the electric field everywhere resulting from two infinite planes with equal but opposite charge densities (Figure 5.26).

Strategy

We already know the electric field resulting from a single infinite plane, so we may use the principle of superposition to find the field from two.

Solution

Show Answer

The electric field points away from the positively charged plane and toward the negatively charged plane. Since the [latex]\sigma[/latex] are equal and opposite, this means that in the region outside of the two planes, the electric fields cancel each other out to zero.

However, in the region between the planes, the electric fields add, and we get

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{\sigma }{{\epsilon }_{0}}\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex]

for the electric field. The [latex]\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex] is because in the figure, the field is pointing in the +x-direction.

Significance

Systems that may be approximated as two infinite planes of this sort provide a useful means of creating uniform electric fields.

Check Your Understanding

What would the electric field look like in a system with two parallel positively charged planes with equal charge densities?

Show Solution

The electric field would be zero in between, and have magnitude [latex]\frac{\sigma }{{\epsilon }_{0}}[/latex] everywhere else.

Summary

- A very large number of charges can be treated as a continuous charge distribution, where the calculation of the field requires integration. Common cases are:

- one-dimensional (like a wire); uses a line charge density [latex]\lambda[/latex]

- two-dimensional (metal plate); uses surface charge density [latex]\sigma[/latex]

- three-dimensional (metal sphere); uses volume charge density [latex]\rho[/latex]

- The "source charge" is a differential amount of charge dq. Calculating dq depends on the type of source charge distribution:

[latex]dq=\lambda dl;\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}dq=\sigma dA;\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}dq=\rho dV.[/latex]

- Symmetry of the charge distribution is usually key.

- Important special cases are the field of an "infinite" wire and the field of an "infinite" plane.

Conceptual Questions

Give a plausible argument as to why the electric field outside an infinite charged sheet is constant.

Show Solution

At infinity, we would expect the field to go to zero, but because the sheet is infinite in extent, this is not the case. Everywhere you are, you see an infinite plane in all directions.

Compare the electric fields of an infinite sheet of charge, an infinite, charged conducting plate, and infinite, oppositely charged parallel plates.

Describe the electric fields of an infinite charged plate and of two infinite, charged parallel plates in terms of the electric field of an infinite sheet of charge.

Show Solution

The infinite charged plate would have [latex]E=\frac{\sigma }{2{\epsilon }_{0}}[/latex] everywhere. The field would point toward the plate if it were negatively charged and point away from the plate if it were positively charged. The electric field of the parallel plates would be zero between them if they had the same charge, and E would be [latex]E=\frac{\sigma }{{\epsilon }_{0}}[/latex] everywhere else. If the charges were opposite, the situation is reversed, zero outside the plates and [latex]E=\frac{\sigma }{{\epsilon }_{0}}[/latex] between them.

A negative charge is placed at the center of a ring of uniform positive charge. What is the motion (if any) of the charge? What if the charge were placed at a point on the axis of the ring other than the center?

Problems

A thin conducting plate 1.0 m on the side is given a charge of [latex]-2.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}[/latex]. An electron is placed 1.0 cm above the center of the plate. What is the acceleration of the electron?

Calculate the magnitude and direction of the electric field 2.0 m from a long wire that is charged uniformly at [latex]\lambda =4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C/m}.[/latex]

Show Solution

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(z\right)=3.6\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{4}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\text{/}\text{C}\hat{\textbf{k}}[/latex]

Two thin conducting plates, each 25.0 cm on a side, are situated parallel to one another and 5.0 mm apart. If [latex]{10}^{-11}[/latex] electrons are moved from one plate to the other, what is the electric field between the plates?

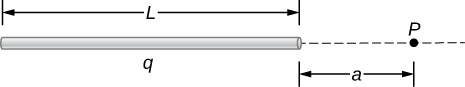

The charge per unit length on the thin rod shown below is [latex]\lambda[/latex]. What is the electric field at the point P? (Hint: Solve this problem by first considering the electric field [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] at P due to a small segment dx of the rod, which contains charge [latex]dq=\lambda dx[/latex]. Then find the net field by integrating [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] over the length of the rod.)

Show Solution

[latex]dE=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda dx}{{\left(x+a\right)}^{2}},\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}E=\frac{\lambda }{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left[\frac{1}{l+a}-\frac{1}{a}\right][/latex]

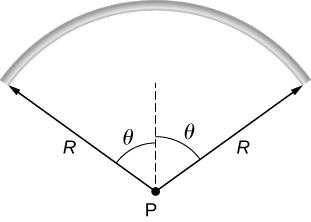

The charge per unit length on the thin semicircular wire shown below is [latex]\lambda[/latex]. What is the electric field at the point P?

Two thin parallel conducting plates are placed 2.0 cm apart. Each plate is 2.0 cm on a side; one plate carries a net charge of [latex]8.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mu \text{C},[/latex] and the other plate carries a net charge of [latex]-8.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mu \text{C}.[/latex] What is the charge density on the inside surface of each plate? What is the electric field between the plates?

Show Solution

[latex]\sigma =0.02\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\text{/}{\text{m}}^{2}\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}E=2.26\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{9}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\text{/}\text{C}[/latex]

A thin conducing plate 2.0 m on a side is given a total charge of [latex]-10.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mu \text{C}[/latex]. (a) What is the electric field [latex]1.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}[/latex] above the plate? (b) What is the force on an electron at this point? (c) Repeat these calculations for a point 2.0 cm above the plate. (d) When the electron moves from 1.0 to 2,0 cm above the plate, how much work is done on it by the electric field?

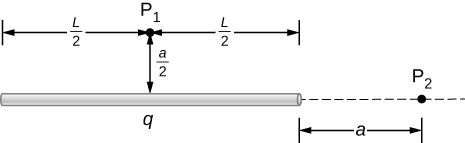

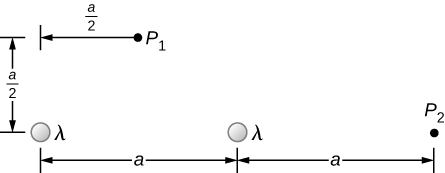

A total charge q is distributed uniformly along a thin, straight rod of length L (see below). What is the electric field at [latex]{P}_{1}?\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{At}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{P}_{2}?[/latex]

Show Solution

At [latex]{P}_{1}[/latex]: [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(y\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda L}{y\sqrt{{y}^{2}+\frac{{L}^{2}}{4}}}\hat{\textbf{j}}⇒\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{q}{\frac{a}{2}\sqrt{{\left(\frac{a}{2}\right)}^{2}+\frac{{L}^{2}}{4}}}\hat{\textbf{j}}=\frac{1}{\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{q}{a\sqrt{{a}^{2}+{L}^{2}}}\hat{\textbf{j}}[/latex]

At [latex]{P}_{2}\text{:}[/latex] Put the origin at the end of L.

[latex]dE=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda dx}{{\left(x+a\right)}^{2}},\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=-\frac{q}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}l}\left[\frac{1}{l+a}-\frac{1}{a}\right]\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex]

Charge is distributed along the entire x-axis with uniform density [latex]\lambda .[/latex] How much work does the electric field of this charge distribution do on an electron that moves along the y-axis from [latex]y=a\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{to}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}y=b?[/latex]

Charge is distributed along the entire x-axis with uniform density [latex]{\lambda }_{x}[/latex] and along the entire y-axis with uniform density [latex]{\lambda }_{y}.[/latex] Calculate the resulting electric field at (a) [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{r}}=a\hat{\textbf{i}}+b\hat{\textbf{j}}[/latex] and (b) [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{r}}=c\hat{\textbf{k}}.[/latex]

Show Solution

a. [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{r}}\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2{\lambda }_{x}}{b}\hat{\textbf{i}}+\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2{\lambda }_{y}}{a}\hat{\textbf{j}}[/latex]; b. [latex]\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{2\left({\lambda }_{x}+{\lambda }_{y}\right)}{c}\hat{\textbf{k}}[/latex]

A rod bent into the arc of a circle subtends an angle [latex]2\theta[/latex] at the center P of the circle (see below). If the rod is charged uniformly with a total charge Q, what is the electric field at P?

A proton moves in the electric field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=200\hat{\textbf{i}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/C}.[/latex] (a) What are the force on and the acceleration of the proton? (b) Do the same calculation for an electron moving in this field.

Show Solution

a. [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}=3.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-17}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex],

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{a}}=1.92\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{10}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}\text{/}{\text{s}}^{2}\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex];

b. [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}=-3.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-17}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex],

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{a}}=-3.51\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{13}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}\text{/}{\text{s}}^{2}\hat{\textbf{i}}[/latex]

An electron and a proton, each starting from rest, are accelerated by the same uniform electric field of 200 N/C. Determine the distance and time for each particle to acquire a kinetic energy of [latex]3.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-16}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}.[/latex]

A spherical water droplet of radius [latex]25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mu \text{m}[/latex] carries an excess 250 electrons. What vertical electric field is needed to balance the gravitational force on the droplet at the surface of the earth?

Show Solution

[latex]m=6.5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-11}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}[/latex],

[latex]E=1.6\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\text{/}\text{C}[/latex]

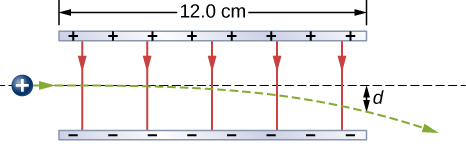

A proton enters the uniform electric field produced by the two charged plates shown below. The magnitude of the electric field is [latex]4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/C},[/latex] and the speed of the proton when it enters is [latex]1.5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m/s}.[/latex] What distance d has the proton been deflected downward when it leaves the plates?

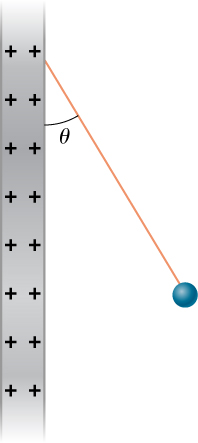

Shown below is a small sphere of mass 0.25 g that carries a charge of [latex]9.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-10}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}.[/latex] The sphere is attached to one end of a very thin silk string 5.0 cm long. The other end of the string is attached to a large vertical conducting plate that has a charge density of [latex]30\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{C/m}}^{2}.[/latex] What is the angle that the string makes with the vertical?

Show Solution

[latex]E=1.70\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\text{/}\text{C}[/latex],

[latex]F=1.53\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}T\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =mg\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}T\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{sin}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =qE[/latex],

[latex]\text{tan}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =0.62⇒\theta =32.0\text{°}[/latex],

This is independent of the length of the string.

Two infinite rods, each carrying a uniform charge density [latex]\lambda ,[/latex] are parallel to one another and perpendicular to the plane of the page. (See below.) What is the electrical field at [latex]{P}_{1}?\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{At}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{P}_{2}?[/latex]

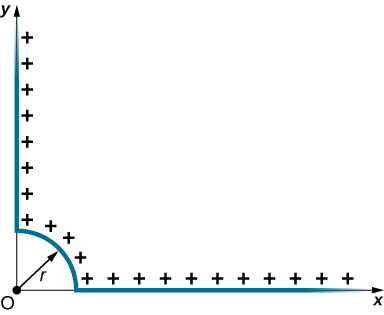

Positive charge is distributed with a uniform density [latex]\lambda[/latex] along the positive x-axis from [latex]r\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{to}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\infty ,[/latex] along the positive y-axis from [latex]r\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{to}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\infty ,[/latex] and along a [latex]90\text{°}[/latex] arc of a circle of radius r, as shown below. What is the electric field at O?

Show Solution

circular arc [latex]d{E}_{x}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda ds}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)[/latex],

[latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{x}=\frac{\lambda }{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)[/latex],

[latex]d{E}_{y}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)=\frac{1}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\lambda ds}{{r}^{2}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{sin}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta \left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{j}}\right)[/latex],

[latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{y}=\frac{\lambda }{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{j}}\right)[/latex];

y-axis: [latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{x}=\frac{\lambda }{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)[/latex];

x-axis: [latex]{\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}}_{y}=\frac{\lambda }{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{j}}\right)[/latex],

[latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{\lambda }{2\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{i}}\right)+\frac{\lambda }{2\pi {\epsilon }_{0}r}\left(\text{−}\hat{\textbf{j}}\right)[/latex]

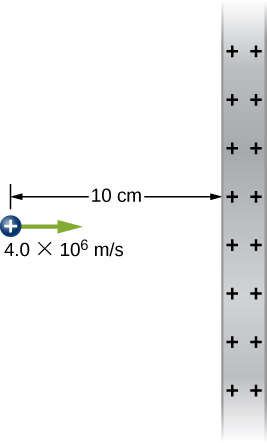

From a distance of 10 cm, a proton is projected with a speed of [latex]v=4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m/s}[/latex] directly at a large, positively charged plate whose charge density is [latex]\sigma =2.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{C/m}}^{2}.[/latex] (See below.) (a) Does the proton reach the plate? (b) If not, how far from the plate does it turn around?

A particle of mass m and charge [latex]\text{−}q[/latex] moves along a straight line away from a fixed particle of charge Q. When the distance between the two particles is [latex]{r}_{0},\text{−}q[/latex] is moving with a speed [latex]{v}_{0}.[/latex] (a) Use the work-energy theorem to calculate the maximum separation of the charges. (b) What do you have to assume about [latex]{v}_{0}[/latex] to make this calculation? (c) What is the minimum value of [latex]{v}_{0}[/latex] such that [latex]\text{−}q[/latex] escapes from Q?

Show Solution

a. [latex]W=\frac{1}{2}m\left({v}^{2}-{v}_{0}^{2}\right)[/latex], [latex]\frac{Qq}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{{r}_{0}}\right)=\frac{1}{2}m\left({v}^{2}-{v}_{0}^{2}\right)⇒{r}_{0}-r=\frac{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}{Qq}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{1}{2}r{r}_{0}m\left({v}^{2}-{v}_{0}^{2}\right)[/latex]; b. [latex]{r}_{0}-r[/latex] is negative; therefore, [latex]{v}_{0}>v[/latex], [latex]r\to \infty ,\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{and}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}v\to 0\text{:}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{Qq}{4\pi {\epsilon }_{0}}\left(-\frac{1}{{r}_{0}}\right)=-\frac{1}{2}m{v}_{0}^{2}⇒{v}_{0}=\sqrt{\frac{Qq}{2\pi {\epsilon }_{0}m{r}_{0}}}[/latex]

Glossary

- continuous charge distribution

- total source charge composed of so large a number of elementary charges that it must be treated as continuous, rather than discrete

- infinite plane

- flat sheet in which the dimensions making up the area are much, much greater than its thickness, and also much, much greater than the distance at which the field is to be calculated; its field is constant

- infinite straight wire

- straight wire whose length is much, much greater than either of its other dimensions, and also much, much greater than the distance at which the field is to be calculated

- linear charge density

- amount of charge in an element of a charge distribution that is essentially one-dimensional (the width and height are much, much smaller than its length); its units are C/m

- surface charge density

- amount of charge in an element of a two-dimensional charge distribution (the thickness is small); its units are [latex]\text{C}\text{/}{\text{m}}^{2}[/latex]

- volume charge density

- amount of charge in an element of a three-dimensional charge distribution; its units are [latex]\text{C}\text{/}{\text{m}}^{3}[/latex]

Licenses and Attributions

Calculating Electric Fields of Charge Distributions. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/5-5-calculating-electric-fields-of-charge-distributions. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction

Source: https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/osuniversityphysics2/chapter/calculating-electric-fields-of-charge-distributions/

0 Response to "Electric Fields of Continuous Charge Distributions Arc"

ارسال یک نظر